Sustainababble

The power of an image

They say a picture is worth a thousand words. I have always found that nebulous and complex issues, which are difficult to convey in words, can be more easily and immediately grasped through the medium of a strong image. I am working on a book about our ‘existential predicament’ and the intention of this work is to combine strong communicative images with well researched and argued writing. In this post, I wanted to share some of the new illustrations I have been working on.

They say a picture is worth a thousand words. I have always found that nebulous and complex issues, which are difficult to convey in words, can be more easily and immediately grasped through the medium of a strong image. I am working on a book about our ‘existential predicament’ and the intention of this work is to combine strong communicative images with well researched and argued writing. In this post, I wanted to share some of the new illustrations I have been working on. I am keen to hear feedback on how successful (or not) you think these images are. So please email me with any comments you may have.

‘GRAZING LAND’ This image was created to represent graphically some statistics on land use which I ran across in George Monbiot's book Regenisis. George makes the point that grazing animals in the UK enjoy around 51% of the total land area whereas we humans are set aside 7%. The more important point he makes is that a meat-based diet requires a huge amount of land area to support it, whereas a non-meat diet needs only a fraction of this amount.

‘TRACTOR’. This image tries to expose the devastating impact that modern industrialised farming practices are having on the environment and, in particular, upon biodiversity. Far from being an 'agricultural miracle', the way we grow food is rapidly degrading the sustaining capacity of the biosphere.

‘WEALTH’ This illustration tries to capture how wealth accumulation in an unbridled capitalist economic system gets dangerously out of balance. According to Oxfam, the richest 1 percent on the planet has pocketed $26 trillion (£21 trillion) in new wealth since 2020. This is nearly twice the acquisition of the residual 99 percent of the world’s population. The richest are getting richer and the poorest are getting poorer.

‘FOR A LIFE WORTH LIVING’. In his book, From What Is to What If, Rob Hopkins suggests that for many, if not most, human beings alive today, we have created the conditions for ‘a life not worth living’. Having created so much societal chaos by having grossly over-populated our planet we need practicable pathways towards a life worth living. That is what I am trying to explore in my new book.

Lewes Home Retrofit Guide

Deeper Green are thrilled to have been involved in the making of this retrofit guide. We provided the illustrations and contributions to the text for this free download publication which was produced in conjunction with Nevill 2030 and the Lewes Climate Hub. The lead authors were Suzy Nelson and Ann Link.

Deeper Green are thrilled to have been involved in the making of this retrofit guide. We provided the illustrations and contributions to the text for this free download publication which was produced in conjunction with Nevill 2030 and the Lewes Climate Hub. The lead authors were Suzy Nelson and Ann Link.

Helping people get more informed around the issues of low-carbon refurbishment is a mission Deeper Green are always keen to help with.

You can download the guide on the following link:

Well, should I get a heat pump?

Ian McKay gives a talk for the Lewes Climate Hub looking in detail at some of the measures you might need to carry out to your property as well as outlines the pitfalls and opportunities of eco-retrofit and heat pump technologies.

Above: Ian McKay at the Lewes Climate Hub talking about heat pumps and what you might need to do to your home to successfully install one.

2023 may turn out to be the year when heat pumps went from being considered in the U.K. as niche heating solutions to becoming a major player in the domestic heating market. Ian McKay was heavily involved in the month-long series of events and exhibition held at the Lewes Climate Hub in November and December 2023. It culminated with a talk he gave entitled, ‘Should I get a Heat Pump?’ and was in fact an updated version of a joint talk McKay gave earlier in the year to another local audience. The talk looks in detail at some of the measures you might need to carry out to your property as well as outlining the pitfalls and opportunities of eco-retrofit and heat pump technologies.

You can watch the edited highlights of the talk, which were filmed and produced by the award-winning film maker, Rowland de Villiers by following this Vimeo LINK.

The importance of ventilation

We need to breathe decent air in our homes. Unfortunately, many of us do not. In this article we look at why we need ventilation, what can go wrong when we do not have enough of it and some of the ways in which it can be provided.

This indicative view makes visible the invisible phenomenon known as water vapour and we generate a lot of it in our homes. Excessive amounts of what in fact is actually a gas need to be ventilated out to reduce harmful effects to occupants and the building fabric itself. Image © Deeper Green

Before the 1970’s most of our homes benefitted from what is called, ‘wind-driven ventilation’ with infiltration through the windward side and displacement on the leeward side. Old forms of construction were 'leaky' with high levels of replacement outside air keeping the interiors refreshed if a little chilly in the winter months.

Then we started putting double glazing in, loft insulation and draught stripping. That in turn led to surface condensation and mould growth. Cases of occupants suffering from asthma and other respiratory illnesses started going up. In response, the national Building Regulations were updated to require ‘intermittent mechanical ventilation’ (extract fans) in bathrooms and kitchens (a.k.a. wet rooms) with background replacement ventilation, usually in the form of trickle vents in window frames.

With a new push to further insulate our walls and eliminate uncontrolled air infiltration, ensuring our homes are provided with adequate means of replacement fresh air and allowing excessive airborne moisture and toxins to escape is becoming more important than ever.

This photograph shows a typical scenario where the conditions for mould growth are initiated by persistent surface condensation forming on the interior face of an external solid masonry wall. This situation can arise with uninsulated cavity wall or a cavity wall with failed injected cavity insulation. Image © Deeper Green

Sources of water vapour

You cannot see water vapour. It is water in a gaseous form and is not to be confused with airborne water droplets like steam or fog. As a gas it can build up to unhealthy levels without notice but when it comes into contact with colder surfaces such as windowpanes or areas of uninsulated walls on a cold day, the moisture condenses out of the gaseous state and into liquid water. Without good ventilation to remove the excess water vapour, building interiors are prone to mould growth, the spores of which can aggravate respiratory conditions like asthma.

This illustration shows a typical scenario where the conditions for mould growth are initiated by persistent surface condensation forming on the interior face of an external solid masonry wall. This situation can arise with uninsulated cavity wall or a cavity wall with failed injected cavity insulation. Image © Deeper Green

In winter, as we try to conserve heat energy, our first reaction is to close windows and seal off vents. The relative humidity in rooms increases, as does the concentration of other airborne toxins, like the CO2 from our own breathing, 'off-gasing' chemicals from materials like polymer-based carpets or pollutants from outside. These will build-up to unhealthy levels making for a 'fuggy' atmosphere.

Trickle vents installed in high performance sliding sash windows as viewed internally from below. Image © Deeper Green

Replacement windows with no trickle vents

If you have a home that has replacement windows with no trickle vents and no ‘whole house mechanical ventilation system’ (see below) then you probably are not getting enough replacement fresh air into your home. In the first instance, one can try manually setting the window ‘ajar’ in the ‘night latch’ position. Most modern casement windows will have this functionality. That maybe too much ventilation depending on the size of the opening casement. Another alternative is to have trickle vents retrofitted and most window fitters should be able to carry this out. Otherwise, and especially if you are considering a more extensive low energy refurbishment of the whole house, you should consider a whole house mechanical ventilation system.

Domestic ventilation options

Here are some of the key forms or domestic ventilation but there are others such as passive stack ventilation (PSV) and positive input ventilation (PIV) but these are generally regarded as more troublesome to get right or ensure consistent performance. Image © Deeper Green

Intermittent extract ventilation (IEV)

Intermittent extract ventilation is the ventilation system that many of us will be familiar with. In the 1970s new Building Regulations were introduced requiring intermittent extract ventilation in wet rooms (kitchens, utility rooms, W.C.’s and bathrooms) and fresh air inlets (usually trickle ventilation fitted in window frames) in living rooms and bedrooms. Gaps under doors are necessary to allow airflow from living spaces into wet spaces. Such extract fans are most often activated by turning on the light switch, but a more effective means of controlling water vapour generally is by linking the extract to a humidity sensor. Some models are quieter than others.

Continuous mechanical extract ventilation (CMEV)

When increasing the standard of insulation and airtightness it may be appropriate to install a more capable form of ventilation to that which IEV can provide. Continuous mechanical extract ventilation extracts stale air from wet rooms at a background level and when relative humidity rises the fan speed increases to a boosted level. When operating at a background level, these extract fans are nearly silent. Such systems can either be decentralised with separate fans in each wet room or with a single fan connected by ductwork to wet rooms. As with an intermittent mechanical extract ventilation, living rooms and bedrooms need fresh air ventilation inlets like trickle vents (these may be wall inlets with humidity sensitive controls) and doors need to be undercut to allow air flow.

Mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR)

Retrofit projects designed to meet the Passivhaus Enerphit standard require the installation of mechanical ventilation with heat recovery. Such systems continuously extract warm air from wet rooms. This then passes through a heat exchanger. Meanwhile a second fan draws in a balancing supply of fresh air which picks up some of the residual heat from the outgoing air as it flows through separate compartments of the heat exchanger before being ducted out to the living spaces.

For the heat exchanger to extract meaningful amounts of outgoing heat energy, the overall external envelope of the building needs to be made virtually air-tight which is technically difficult to achieve even with a new build. Such an installation will involve finding space to accommodate a box containing two fans and a heat exchanger and ductwork connecting all rooms, which can be difficult to accommodate in an existing dwelling.

Governance

To ensure we have a reliable trajectory towards a steady state existence on the planet, we need systems of governance which are fit for purpose in so far as they can create and maintain a framework for this momentous transition to take place. This new order and capability will have to tame the rapacious tendencies of free enterprise and kerb the misinformation potential of power-hungry candidates on the campaign trail. It will also have to win back confidence in the validity and fairness of the system itself.

“Democracy is the worst form of government except all those other forms which have been tried from time to time.”

Winston Churchill, Speech in the House of Commons, 11 November 1947

Introduction

To ensure we have a reliable trajectory towards a steady state existence on the planet, we need systems of governance which are fit for purpose in so far as they can create and maintain a framework for this momentous transition to take place. This new order and capability will have to tame the rapacious tendencies of free enterprise and kerb the misinformation potential of power-hungry candidates on the campaign trail. It will also have to win back confidence in the validity and fairness of the system itself.

We can look at all the forms of government which have been tried including democracy, meritocracy, oligarchy, autocracy etc but which typology is going to work best in delivering what is needed and be the least unpalatable? Can any useful tweaks be added to existing systems of governance? Churchill memorably defended democracy as the least flawed of what has been tried. That may have been the case in the late 1940’s world order, where post-war states could look forward to the bounty of neo-liberal economic ‘miracles’ whilst ignoring the future consequences of over-consumption. In our current state with over eight billion people sharing the diminishing resources and eco-system of Earth, politically unpopular things may need to be done to responsibly respond to the climate change emergency and eco-system collapse. Changes in the way we govern our human race must surely be looked at.

Above: The never-ending spiral of woe in the 2020’s is testament to the 70+ years of neoliberal growth-based economics and unmanaged human population growth – it’s all connected.

It is all connected

Climate change is a symptom but not necessarily the cause of why we have an existential crisis. The reason we have climate change is now indisputably mostly down to human impacts. Therefore, responsible governance at all levels is needed to steer, regulate and, if necessary, police our transition to a steady state existence supportable by the Earth’s eco-system services.

No matter what part of the world you live in, the pressures of over-consumption, over-population as well as the increasing effects of climate change will affect everyone – even in economies and climates which might feel relatively insulated from the gravest impacts. The more climate change, the less arable land and the more people who will be displaced. The more human impacts, the less resources and ecological sustaining capacity will be around to support us. It is all connected and inescapable. The impacts are now so obvious that it is becoming increasingly difficult for corporate and political misinformation campaigns to deny that human activity is the primary cause of eco-system collapse.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), an annual average of 21.5 million people have been forcibly displaced by weather-related events – such as floods, storms, wildfires and extreme temperatures – since 2008. These numbers are expected to surge in coming decades with forecasts from international thinktank the IEP predicting that 1.2 billion people could be displaced globally by 2050 due to climate change and natural disasters.[1]

Taming the free enterprise beast

In a way, the increasing degree of governance required is proportional to the higher the density is of human population. Additionally, the scarcer our remaining resources get and the less able the environment is to absorb our generated pollution and waste, the more organised we will have to be in metering out the equitable shares.

It is not so very long ago that the ‘wild west’ of the United States of America was a land untamed by the civilising laws of the pilgrim descendants and European settlers. By overpowering the first nations people that were already there, it was a landscape big enough to create one’s own economic system, pretty much make your own laws and ignore the environmental consequences. It is the idealistic basis of what many people hold dear when they think of American freedoms. To avoid outright anarchy, the more populated that ‘wild west’ landscape became, the more rigorous and controlling its laws and forms of governance had to become.

Businesses are often the first to realise that things need to radically change to be on a more sustainable footing but they are reluctant to do so if the playing field becomes uneven and tilted in favour of their competitors. That becomes tricky when it crosses borders. International cooperation must work rapidly to re-grade the economic setting for a steady state environmental existence to be achieved.

Above: Reward miles schemes are loyalty schemes but they are also drivers of overt planetary degradation where marketing polish helps underpin consumer air travel as a perfectly acceptable and guilt-free social norm.

The corporate world will defend its corner and in certain sectors, which maybe wholly incompatible with a steady state planetary existence, their motives to grow their business will conflict with our societal transition away from a fossil fuel-based economy. Take the aviation industry. So far there is sadly no viable truly low-carbon let alone zero-carbon form of air travel although many will hang its future on hydrogen fuel. Airlines and the wider travel industry are completely free to pitch for all the passenger traffic they can get. To keep customers loyal, they have been using reward miles or frequent flyer schemes. It is all done with a corporate marketing polish which makes air travel look like a completely reasonable guilt-free societal norm. The overall effect though is to encourage consumers to ever increase their ecological footprint.

So another crucial role that governance could play is in assessing the environmental impact of an industry relative its societal worth. Is it a ‘must have’ or ‘nice to have’? This will mean our ‘free-market’ value system will need recalibrating.

So another crucial role that governance could play is in assessing the environmental impact of an industry relative its societal worth. Is it a ‘must have’ or ‘nice to have’? This will mean our ‘free-market’ value system will need recalibrating.

Start at the global scale

Above all else, global cooperation is imperative. All nations must come together and take real and responsible action. It is no use ‘global south’ blaming ‘global north’ and vice versa. Recent C.O.P. conferences are testament to this but unless, responsible action is taken, it could be interpreted as a bunch of nation states rather flippantly demonstrating for posterity that, “at least we tried”. What we mean by ‘responsible action’ is surely to transition away from growth-based economics to encompass ‘behaviour change’ and managed population decent as per the suggestions from the 1972 Limits to Growth study published by the Club of Rome.

Of course, we cannot seriously expect our western democracies to just give up on growth and say ‘goodbye’ to the unprecedented raising of living standards seen since the post-war world order was created. So far mainstream politics have strongly rebuffed de-growth and steady state economics. What has been happening for some decades now is the necessary actions being ignored and side stepped and red herring issues thrown up to obfuscate the debate. We already see world leaders turning around to their own electorate and blaming other sovereign states for inaction or not living within their remaining carbon budgets. Some governments who desire power over a responsible legacy will simply say to their voters, “Don’t listen to those climate scientists. What our economy needs is growth, I’ll make your living standards better. Vote for me.”

How can global cooperation around responsible action then be a realistic goal?

We are on a highway to climate hell with our foot on the accelerator. We need all hands-on deck for faster, bolder climate action. A window of opportunity remains open, but only a narrow shaft of light remains... We are getting dangerously close to the point of no return.

UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, Speech at the COP 27 conference, Egypt 7 Nov 2022

As part of the post-war world order, the United Nations was created, taking over from the League of Nations. Being a U.S.-centric construct, it has its detractors but it is certainly the most obvious and powerful of existing global forms of governance we have. It is an assembly now of over 190 member countries bound by a treaty dating from its formation in 1945 with numerous amendments but with limited legislative powers over sovereign states. It is like a guardian with a rabble of unruly children to look after but without the power to send any of them to the naughty step. It can however deliver a good telling-off. Indeed, U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres resorted to as much by addressing world leaders at the opening of the C.O.P. 27 conference in Egypt in November 2022, saying, “We can sign a climate solidarity pact, or a collective suicide pact… The global climate fight will be won or lost in this crucial decade – on our watch.”

In 2015, the UN launched its Sustainable Development Goals. This was a major step towards directing global action on addressing the human predicament on planet Earth. It consists of 17 goals:

GOAL 1: No Poverty

GOAL 2: Zero Hunger

GOAL 3: Good Health and Well-being

GOAL 4: Quality Education

GOAL 5: Gender Equality

GOAL 6: Clean Water and Sanitation

GOAL 7: Affordable and Clean Energy

GOAL 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

GOAL 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure

GOAL 10: Reduced Inequality

GOAL 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

GOAL 12: Responsible Consumption and Production

GOAL 13: Climate Action

GOAL 14: Life Below Water

GOAL 15: Life on Land

GOAL 16: Peace and Justice Strong Institutions

GOAL 17: Partnerships to achieve the Goal

One suspects much lobbying was applied to its final wording and ordering. The order of numbering implies a hierarchy of prioritisation. It is notable that the first 12 goals are human-centric and action on climate change is demoted to Goal 13. The natural world does not get a mention until Goals 14 and 15 respectively. Still, it is a start and it is particularly encouraging to see that in Goal 12 the issue of Sustainable consumption and production is tackled.

Sustainable consumption and production is about doing more and better with less. It is also about decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation, increasing resource efficiency and promoting sustainable lifestyles.

The U.N. set up the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 1988, providing regular assessments on the rate of climate change and its impacts and risks. It also assesses options for adaptation and mitigation. This is a truly global effort with scientists and experts contributing from all corners of the planet.

Since 1995, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has promoted action on climate change by holding annual U.N. climate change conferences. Formally this is known as the Conference of the Parties or C.O.P. for short. Additionally, the U.N. has held climate action summits.

However, the legacy of the U.N.’s global environmental cooperation work, stretches back much further. In June 1972 the U.N. Scientific Conference was held in Stockholm. Also known as the First Earth Summit, it adopted a declaration setting out the principles for preserving and enhancing the human environment and the issue of climate change was raised for the first time. Another significant milestone was the Montreal Protocol of 1988 which successfully tackled the control of ozone depleting gases following the discovery in 1987 of a rapidly expanding hole in the Earth’s atmosphere over the south pole. This is still seen as one of the greatest achievements of global environmental cooperation. The Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit in 1992 became famous for setting out Agenda 21 which specifically targeted the protection of the atmosphere. The conference also resulted in signing-up 158 states towards the establishment of the aforementioned UNFCCC.[2]

A cornerstone achievement of the C.O.P. summits is probably the 1997 Kyoto Protocol which effectively formed the legal framework for individual countries to reduce industrialised greenhouse gas emissions by at least 5% below 1990 levels between 2008 and 2012. Another major milestone is The Paris Agreement of 2015 which had the goal of limiting global warming to “well below 2, preferably 1.5 degrees below Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels.”[3] It requires signature countries to a 5-year cycle of increasingly ambitious climate action.

So, the U.N. is the established global body of governance and is certainly trying hard to reach consensus on responsible climate action and good custodianship of the planet’s resources and eco-system. Its weakness lies in its inability to hold member states truly to account and its ambitions and decrees are subject to special interest lobbying. Can it morph into the regulatory framework that bold, responsible and rapid climate emergency response demands?

The transition between global and sovereign governance

As part of the M.I.T. programming of the World 3 computer model which derived the Limits to Growth Study of 1972, the researchers anticipated what they coined ‘decision delay’ into their projections. This has turned out to be particularly relevant to real world governance events in the fifty years since as evidenced by President Trump’s election pledge to withdraw from The Paris Agreement. In June 2017 he signed an executive order to commence that extrication. He cited that the Paris Agreement would “…undermine…” the U.S. economy and put the U.S. at a “…permanent disadvantage.”[4] One is left to wonder how much environmental damage and planet degradation ensued before Trump’s presidential successor, Joe Biden signed the U.S. back into the agreement with another executive order in January 2021. This example of decision delay is so important as we are already locked-in to tipping points of climate change, habitat depletion and species extinction. Every day lost really matters now.

To avoid this kind of ideological swinging and climate action derailment from happening in democracies, we need additional checks and balances brought in at the global and national level. Sanctions on a global stage with real teeth need to be there to deter reckless electioneering for the popular vote at the national level.

Is sustainability too grave and too complex for conventional democratic processes?

The established way the U.K. approaches its climate response is to have government advisors and scientists present their research and forecasts from their respective silos of interest and then the government of the day creates policy to respond in a way which best meets their manifesto pledges and political ideology. In extreme cases that would be to almost ignore the expert advice of existential threat completely in favour of ‘growth, growth, growth’ which was pretty much the case with the election pledge of Liz Truss in the summer of 2022 who (worryingly) courted the most votes from Conservative Party members.

The rise of the popularist movement and the demonising of the so-called ‘establishment’ suggests that the electorate too need to be more responsible with their vote, endeavour to understand better what it is they are voting for and what the wider implications might be. The U.K.’s Brexit referendum is a clear example of the where the electorate made a decision without fully understanding or believing the implications. Most voters were prepared to believe a flippant and misleading slogan on the side of a campaign bus rather than to listen to recognised economic experts. The arguments to leave the European Union were easy to make into simple catch phrases that easily engaged the discontented popular vote. The reasons for staying within the E.U. however were far more difficult to communicate and the messaging struggled to be heard above the Europhobic rhetoric. Just over half a decade in and Brexit is becoming a momentous example of democratic self-harming.

The truth is that matters such as Brexit or climate emergency response are exceptionally complicated and indeed grave. Is it not a bit much to expect everyday voters to be enough informed on the myriad of issues at stake to make sensible and balanced judgements about them, particularly through the something so crude as a referendum?

The new corrupting threats to democracy

Democracy is battling with new and distributing forms of misinformation in the digital/internet age. Misinformation is not a new concept. Rulers, especially conquering ones, have re-written their preferred versions of history for millennia. This new technology has hit society quickly, and our existing systems and processes are barely able to keep up. It affects the way society thinks and of course votes. It is undermining press freedom and is also being used to interfere directly in the process of voting itself to the point where mistrust in the system is rampant.

In countries which claim to have a ‘free press’, a game of cat and mouse has built-up whereby the press claim to hold the government of the day to account. With the threat of being branded, ‘fake news’ just a tweet away, it is getting harder for traditional journalists and conventional channels of press communication to be believed or even listened to. Their ability to hold politicians to account, even in ‘free-countries’ is becoming increasingly marginalised.

Another deepening flaw of most forms of governance (not just democracy) in a world with increasing disparities of wealth and power is that governance can veer closer and closer to autocratic or oligarchic tendencies. With this comes increasing levels of corruption and information control. How much of the truth is made available to the public with this form of governance will depend on how confident those in power are of revealing it. Putin’s Russia is a case in point. Russia would claim to be a democracy but most of the rest of the world would call it an oppressive autocratic regime.

Using information platforms on the internet, conspiracy theorising has been on the rise. The most famous of these is the QAnon posts which started in 2017 in the U.S. Seen as a far-right movement to smear politicians, government officials, celebrities and business tycoons, it stirred-up hate by linking targeted people to a global cabal involved in satanic child abuse. QAnon supporters later became involved in Donald Trump’s ‘Stop the Steal’ campaign and then the storming of the U.S. Capitol Building on 6 January 2021.[5] In December 2022, a right-wing plot was uncovered to takeover Germany’s Bundestag. Members of the extremist Reichsbürger [Citizens of the Reich] movement were said to be modelling their governance on the Second Reich established in 1871.[6] Contemporary polling in Germany suggests that as much as 20% of the population are open to conspiracy theories. This is cited as an accelerated phenomena following the Covid-19 restrictions.

Also in December 2022, EU officials were arrested under charges that they accepted bribes from Qatar in return for gaining influence. Roberta Metsola said that "open, free, democratic societies are under attack". [7]

Big business has long established a means of influencing government. Certainly, in the U.K. and the U.S. it is completely commonplace and above board for wealthy doners to sponsor election campaigns and donate towards the political parties they feel have the most chance of getting into power.

Whilst it spends heavily on directly lobbying government, commercial interests also look to affect public /voter opinion. One technique long-established is to buy column space in newspapers, often in the form of ‘advertorials’ and these are designed to look like the publication’s own output. The main purpose of these is to influence public opinion. Exxon, the Global Climate Coalition and the American Petroleum Institute, to name but a few, all did this as part of a mis-information campaign to spread doubt about the legitimacy of climate-change science, as was brilliantly revealed in the BBC’s documentary, Big Oil v the World aired in July 2022.[8]

What lessons can be learned from China

China is even more conscious about information flows than Russia although it does not see itself as a democracy nor an autocracy. This once impoverished communist state which has older and very different value systems to the west, has evolved into a socialist meritocracy which openly encourages, somewhat bizarrely, free-enterprise activities that might normally be associated with a democratic state.

Western powers would see China more as an authoritarian government rather than a meritocracy along the lines of Confucian ideals. The Chinese would say their system works for them but to maintain it, the State sees fit to throttle free speech. Foreign information networks are banned in mainland China. For Chinese leaders, information is seen as dangerous.

That said, the Chinese state do seem to understand the need for responding urgently to climate change. By being the ‘world’s factory’ for well over two decades, China has become a super cash-rich power. It has afforded itself a far quicker technological transition towards a renewables-based economy than the west. It may still be building coal-burning power stations but it already outstrips the U.S., Japan and Australia for the percentage mix of renewable power generation within its electrical grid, according to Enerdata[9]. Unlike countries like the U.K. which have a tiny industrial base by comparison, China continues to manufacture much of the stuff the rest of the world consumes and for this it needs huge amounts of energy and resources. An oppressive regime it maybe, but with its form of authoritarian meritocracy it has determined to ensure that all its city taxis, buses and motorbikes are already running on non-fossil fuels. No democratic country has yet achieved that.

The Chinese would argue that their form of governance is a much better fit for steering economies away from over-depletion of the planet. While democracies try their best with four or five-year political cycles, the Chinese can set much longer-term strategies towards resource and food security, power generation and energy efficiency programmes. Returning to the climate agreements and the signatories of them, how does China know if the U.S. or another major economic player with a democracy is not going to excuse itself from the table again when things get tough with their electorate?

The European Union’s international, multilingual, political institution

What about the European Union? It has evolved from an assembly (akin to the U.N.) to a form of parliamentary democracy. Impressively it is an international, multilingual, political institution of currently 27 countries which has increasingly gained in responsibility and legislative clout as it works towards ever closer economic and political union. It is composed of directly elected representatives (M.E.P.s) by voters of member states with the remit of overseeing E.U. law-making. It is supported by a Secretariat which is in effect the E.U. civil service. Here the administration provides the technical assistance to the M.E.P.’s in delivering their work. In many respects it is an astonishing achievement to have so many countries in a region of the world which less than 100 years ago was witness to total war. In many respects it is a crowning testament to the post-war European peace effort.

The E.U. takes what the U.N. does as an organisation but goes further to operate in a more coordinated political fashion. Reaching accord on policy is fraught with many opposing national opinions. Decision delay and compromise are unavoidable outcomes. Some countries are more divergent from the core consensus than others and trickier projects are simply left on back-burners.

The hugeness and remoteness of the E.U. parliament is for many, particularly among Eurosceptics, a massive problem. It is supposed to operate in a democratic fashion but the impression at grass roots level is that its institutions, and the matters it deals with, are too remote to be properly engaged with by voters. It appears as an unaccountable regime dressed up to look like a democracy. On the other hand, it is an evolving project and in many ways it has the sort of coordinated governance required to deal with a trans-national climate emergency response.

Cross-party working groups

There have not been many mooted solutions to shaw-up the increasingly dodgy ground that democracies find themselves on. There are some vehicles of process which might help in this regard. One such candidate might be to make better use of cross-party working groups. We often hear about them being set-up to look at challenging policy issues that go beyond the concerns of party politics and into the realms of responsible societal governance. Their findings are not policy but advisory resumés of the context and possible ways forward. Unless we hear about their work in the press, the workings of such groups are largely outside of popular engagement.

As an amendment to sovereign constitutional processes, perhaps their use should be more formally recognised and promoted.

Thinktanks and policy institutes

Thank tanks have been around since the 19th Century, first emerging in the United Kingdom and then America and the rest of the world. They proliferated after the WWII and then again in the policy vacuum created after the Cold War and with the emergence of ‘globalisation’.[10] Sometimes they are ‘arm’s length’ entities of government but more often they are formed out of corporate interests. To give them extra kudos their financial backers might establish them in well regarded institutions of learning. Whilst they may come up with interesting research and policy suggestions, their roots are almost all associated with vested interests and perhaps not the neutral influence that is needed.

Citizen’s assemblies

One relatively new innovation which might provide democracies with a much-needed knee-up is the creation of citizen’s assemblies (C.A.s). There are already many around the world that have specifically been looking at climate change and the associated societal responses.

A citizen’s assembly seems to be a very similar construct to that of a jury in a legal or criminal hearing. Members of a C.A. should be drawn from all walks of life and picked in a similar way to how a jury is assembled. The C.A.s then start to interrogate the relevant matter they are charged with. They hear the evidence of experts and specialists in the relevant fields of enquiry as a jury might listen to witnesses in a criminal trial. The C.A. then go on to agree a set of recommendations - not necessarily a verdict passed onto a presiding judge. Their findings are addressed to the appropriate levels of government for their further consideration which may or may not be be taken forward into a policy response.

In the U.K., governance relies heavily on civil servants to support policymaking and delivery and ensure a smooth transition between one government and another. They are a form of check and balance already established but their recourse to blowing the whistle when their political masters go too far off-piste is not a regulated one as their official remit is to support the Government of the day in delivering their political ideology. A C.A. might be a more open and transparent arbiter with a freer hand to go the press, as it were.

The important aspect of the citizen’s assembly system is that it must be seen as a representative cross-section of the electorate. It must be overtly democratic and transparent in its processes. Unlike a simple election, where voters elect a representative to look at challenging and complex issues on their behalf, the C.A. itself is charged with that unpacking and compiling of recommendations. It is therefore a responsible additional influence, albeit limited to an advisory role, on a democratic system which is increasingly open to fraud, corruption and polarisation. In the face of social media distrust and misinformation, C.A.s should help build-back confidence in the ethics of their government’s decision-making. Most importantly of all in the context of governance during a climate emergency, is that a C.A.s evidential advice will help politicians deliver policy objectives which, in many cases, maybe of an uncomfortable direction for many within the electorate.

[1] https://www.zurich.com/en/media/magazine/2022/there-could-be-1-2-billion-climate-refugees-by-2050-here-s-what-you-need-to-know#:~:text=These%20numbers%20are%20expected%20to,climate%20change%20and%20natural%20disasters.

[2] https://www.un.org/en/chronicle/article/stockholm-kyoto-brief-history-climate-change

[3] http://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_withdrawal_from_the_Paris_Agreement

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/QAnon

[6] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-63885028

[7] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-63941509

[8] https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p0cgqlvk/big-oil-v-the-world-series-1-3-delay

[9] https://yearbook.enerdata.net/renewables/renewable-in-electricity-production-share.html

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Think_tank

Hunting for a cheap to heat house?

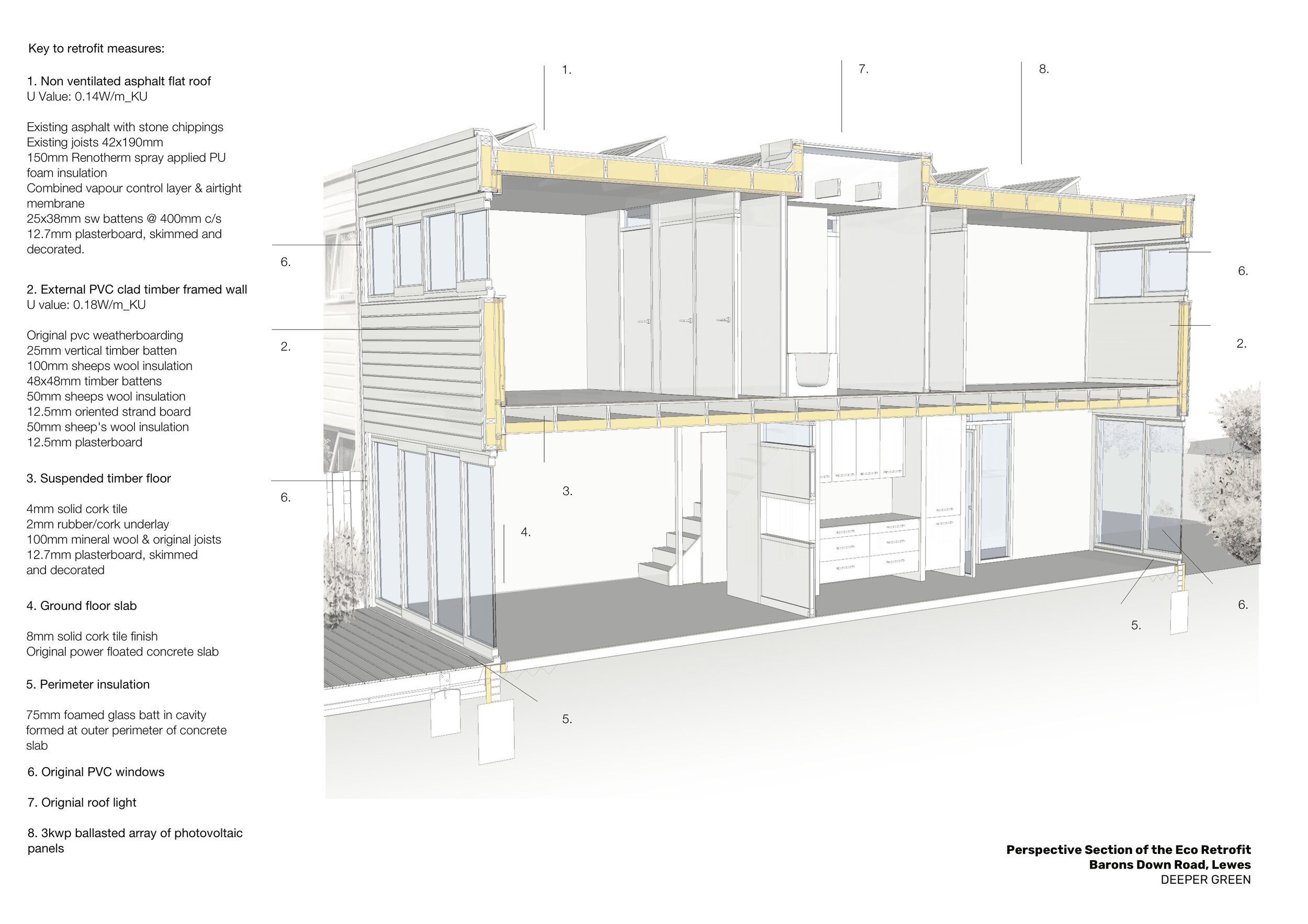

Above: The award winning eco-retrofit of a 1960’s built timber frame house in Lewes, East Sussex as shown in a sectional perspective. For a budget of less than £70K including solar panels and VAT, the house was made virtually carbon neutral and almost energy cost neutral. As a mid-terrace flat roofed timber framed house, it was an ideal candidate for cost effect eco-refurbishment.

With the advent of the new PAS2035 – Specification for the Energy Retrofit of Domestic Buildings, the UK is having another go at mass eco-retrofit. Here are some top tips towards a successful eco-retrofit starting with what kind of property you should try and find if you fancy having a go.

Don’t stretch your budget too thinly

It is fair to say that the most common enquiry an architect will receive in the private residential sector is a couple who have bought a house and they want to add an extension and they want to make the rest of the house more energy efficient. Nine times out of ten, their budget will be insufficient to do both elements well and normally they end up just making the extension and the house remains expensive to heat. Everyone wants more space of course and whilst people can afford their energy bills, they will likely go for the extension over the eco-retrofit when push comes to a budgetary shove. Perhaps in the energy starved future ‘adding value’ to a house in real estate terms will not just be about how many additional rooms you may have added but to demonstrably show how energy efficient and cost effective the building is to live in.

The less surface area the better

A terrace house is one of the most cost effective typologies you can get as you only really need to treat the external facing elements of the ‘thermal envelope’. It is even better if it has a well orientated (within 30º of due south) pitched roof facing south either on the front or garden elevations.

The humble mid-terraced property is your best bet because you simply have less external wall to insulate. However, be careful of terraced housing with large rear extensions (also known as ‘outriggers) – with their shallow but long floor plans and lots of external walls they are particularly parky in winter. If you have a detached, semi-detached or end of terraced property, you will have more external surface area to treat.

Steer clear of charming but fussy architectural detailing

Sadly, if the property has lots of charming but fussy architectural articulation, this will likely be expensive to deal with when it comes to insulating the walls. If it is on the outside you may also find the local authority are not too keen on you changing it or covering it over. If you are insulating on the inside, you may override the charm of the period features or need to have them reinstated with a small loss of floor area.

Eke out a timber frame

Importantly for a refurbishment, it is usually easier to carry out an energy efficient refurbishment on a timber frame building than on a masonry one and the key to that is ensuring you keep the constructions BREATHABLE. However, in the UK there has been a lot of predominantly unwarranted resistance to timber frame construction. It is true a lightweight timber frame building can be prone to overheating if the glazing is poorly protected against too much unwanted solar gain and/or the structure is under insulated. That said it is quick and easy to heat up.

There are a lot of people who espouse the benefit of heavy thermal mass when it comes to energy efficiency – solid brick, stone, blockwork or concrete will give you that. The idea being is that once you’ve loaded up the internal fabric with the heat energy or ‘coolth’ to provide thermal comfort, the building will not be too much affected by big fluctuations in outside air temperature between day and night. Of course, this also means you have to insulate to the outside of the mass really well, so your building does not hemorrhage the energy. This has to be taken with moderation. Too much thermal mass will give you internal condensation issues, particularly in the warm season – counterintuitive though it may seem. It will be interesting to see what the insurance industry makes of poorly conceived eco-retrofits of traditional brick buildings relative to well-designed timber framed houses in the years to come.

Try to avoid buildings where internal insulation is the only allowable solution

In many instance, insulating an existing external wall is only practicable from the inside. In this case it is solid brick.

When it comes to insulating external walls, it is always more efficient and technically safer to insulate on the outside of a property than on the inside faces. If you insulate the inside faces you will have the risk of creating stale moisture behind the cladding and this may lead to mould growth and possibly fungal attack of the building fabric. Conservationists should take note that if you insist on a brick or stone building being insulated internally, that stone or brick will stay colder and wetter for longer with an increased risk of frost damage. If you have timber joists socketed into the brick, these should be cut back and the load transferred to the sidewalls and that is expensive to execute. The best type of internal insulation is a breathable one. If you can get the moisture in the wall to transpire to the inside as well as the outside, it should be safer. The only other watch point is not to insulate internally too much. Super insulating on the inside of a masonry building will increase the risk of defects arising. The aim should be to just to take the edge off those ‘stone cold’ surface finishes. Calcium silicate boards, timber fibre insulation with lime plaster and cork linings or cork plaster can achieve just that.

Hunt for a property with plenty of access to the sun

Roof typologies which are well suited to collecting free solar energy.

If you want to take advantage of free energy from the sun, look for a property with plenty of sun. A south-facing slope with little overshadowing buildings or trees is ideal. Also check how the building is orientated with the sun. If you have large amounts of glazing facing south, then you can look forward to plenty of free passive solar heating in the colder months. South facing glazing is also easier to protect against too much solar gain in the warmer months with external blinds, shutters or even foliage. East and west are tricky as the sun is lower in the sky when it enters the glazing and easy horizontal solar shading solutions above the glass do not tend to work. Large amounts of west facing glazing are perhaps to be avoided or changed. Check out the roof and make sure it can accept plenty of solar panels with minimal overshadowing and predominantly facing south. Hips, dormers and chimneys are not great when it comes to an efficient array of solar panels.

Awkward roof forms will also tend to limit the amount and the efficiency of a solar panel installation.

Glazing

If heritage styling is important, remember that it can negatively effect the outcome of a property’s potential to exploit natural daylight and beneficial solar gains.

For years, double glazing was always seen as one of the biggest energy-saving features you could install on a property. Nowadays, almost all dwellings in the UK have double if not triple glazing so it is a case of diminishing returns if you replace knackered units. One good rule of thumb with glazing is to maximise glazing on the south side (as mentioned above) and have smaller penetrations on the east, west and north elevations. Some energy consultants also promote running with double glazing on the south side and having triple glazing on the other elevations. If the passive solar gain on the south side works well through the year then this makes a lot of sense as triple glazing will actually reduce the solar gain coming through. Triple glazing is more expensive than double glazing, but it may surprise many at how little extra it is.

Heating and power

In 2020 the electricity grid is only partially decarbonized. Until it is more fully carbon neutral, if your property has mains gas, you might be best off sticking with a high efficiency gas condensing boiler for a little longer. Heat pumps work off electricity and crudely they work a little like a refrigerator in transferring heat away from either outside air, the ground or a body of water and, with a bit thermo-dynamic magic, dump that heat into your space heating and domestic hot water tank. The technology is still very expensive to purchase compared with a gas boiler and, until the grid is more fully decarbonized, it is perhaps more carbon beneficial to stick with a gas boiler, although that argument will not be valid for much longer.

Solar thermal panels are good value. If you have room to mount a couple of panels on the roof and have a hot water cylinder in the house, you can get about 50% to 60% of your dwelling’s domestic hot water needs through a solar thermal installation.

Solar photovoltaic panels are the type that make electricity. That said, you need about 8 to 12 panels to have a worthwhile amount of power generated for a house. You also need what is called an inverter internally. This takes the DC power from the panels and converts it to AC power so it can go into the mains power supply and also be fed back into the grid. You can fit electric storage batteries or dump excess electricity into your hot water cylinder, though arguably that is a very poor conversion of energy.

In traditional central heated house, we have relied on a boiler using bio-mass or fossil fuel to provide the heat energy input to provide thermal comfort when the rate of heat loss through the building’s fabric in cold weather starts to accelerate.

In a super-insulated house the rate of heat loss is slowed down to such a point that in some instances it is possible to heat the building with body warmth, cooking and the odd electric heater. This is the principle behind the Passivhaus standard. To do this with a retrofit project is a big and possibly very expensive undertaking.

It is always worth remembering when thinking about heating and power, the so-called, ‘fabric first’ principle. That is to say, try and get the heating and power load of the building as low as practicable before you look at other technology.

Ventilation

It is important to ventilate your habitable spaces. Stale air can be unhealthy for the occupants. In winter, even if you have a well-insulated house, you still have to bring in cold fresh air. For this reason, you might want to consider mechanical ventilation. If you do a really good low carbon refurbishment, you should also try and eradicate unwanted air leaks through the fabric of the building – areas between external windows, doors and walls or service penetrations. If you can get the air leakage rate down to under one air change per hour (difficult to do) then you might want to consider mechanical ventilation with heat recovery. This expensive and very invasive technology may not be all that practicable to install in an existing building as you have to run air ducts to the habitable rooms, bathrooms and kitchen. It is however considered more energy efficient than passive ventilation. If your budget or the constraints of the project do not allow for this, ensure the glazing installed has trickle vents.

Low energy lighting

The advent of LED lighting technology has revolutionized how we light buildings in recent years. Even in the early 2000’s LED lighting was not really capable of being the main lighting source for a room. They just were not bright enough. All that has changed. They provide superb quality and quantity of light without flicker and incredibly long service life – no more changing bulbs. Best of all though is how much more energy efficient they are than the old tungsten filament lamps. You can light a three-bedroom house for under 200 Watts!

Climate change adaptation

The experts say our weather patterns will change quite significantly over time. There will be longer and more intense periods of sun and rain that in turn will stress a building’s fabric yet further. Rainwater goods may need to be replaced with larger profiles to handle more intense rain events. Increased ultraviolet intensity will accelerate the degradation of some external materials. Older buildings may yet perform better than some of our more recent commercial offerings particularly in protecting the occupants against unbearable overheating. If many of our houses then require energy for comfort cooling in the summer as well as for heating in the winter, our efforts towards creating cheap to heat buildings will be environmentally meaningless.

Teleworking Cities of To-Morrow

An idea who's time has come

During the early stages of the Coronavirus lock-down, the RIBA Journal decided to launch a competition posing the question of how do we live with this virus going forward? The competition was called, 'Rethink: 2025 – Design for life after Covid-19'. In the run-up to launching Deeper Green, founder Ian McKay decided to dust off an idea he originally mooted in the late 1990's through his former practice, BBM Sustainable Design. In its original guise, the idea was known as the Comstation and it was an idea targeted at helping society reduce its dependancy on commuting with view to lowering carbon emissions. Twenty odd years on, it would appear society just was not ready for it. Perhaps with the enforced working from home regime of the first half of 2020, its time has come. In its updated format, now called The Node, the proposition thinks through issues around living with the Covid-19 pandemic.

Above: Ebeneezer Howard's famous 'Three Magnets' diagramme as reimagined for a teleworking city of to-morrow.

An idea whose time has come

During the early stages of the Coronavirus lock-down, the RIBA Journal decided to launch a competition posing the question of how do we live with this virus going forward? The competition was called, 'Rethink: 2025 – Design for life after Covid-19'. In the run-up to launching Deeper Green, founder Ian McKay decided to dust off an idea he originally mooted in the late 1990's through his former practice, BBM Sustainable Design. In its original guise, the idea was known as the Comstation and it was an idea targeted at helping society reduce its dependancy on commuting with view to lowering carbon emissions. Twenty odd years on, it would appear society just was not ready for it. Perhaps with the enforced working from home regime of the first half of 2020, its time has come. In its updated format, now called The Node, the proposition thinks through issues around living with the Covid-19 pandemic.

Transitioning out of the age of the commuter

There are of course two existential societal threats that we currently face, Coronavirus and the climate change emergency. We therefore must exploit the positive environmental changes we have all witnessed these last few months while we get the society back to work and school. So this proposal concerns two sectors effected by the Coronavirus outbreak. One is transport, where the lockdown gave us a unique insight into how society could cope with far less mobility, and the other is the service sector which perhaps most easily of all sectors adapted to the limitations of homeworking.

The main premise of this proposal is to nurture a society where about 70 per cent of the working population telework roughly 70 per cent of the time with a view to reducing carbon emissions and improving quality of life.

In the 19th Century, the UK pretty much invented the Age of the Commuter and the town and country idyll which was emulated the world over. Since the mid-1980's the transport sector has become the UK's biggest polluter. Politicians and business leaders alike have pretty much turned a blind eye to our unbridled use of transport. We love it. We are mobility junkies.

Above: Since the mid-1980's the transport sector has become the single biggest emitter of carbon in the UK and continues an upwards trend.

In the last 40 years, the Information Age has arrived. Whilst some hinted that teleworking could start to replace commuting, there has been little interest in exploiting the potentials for social and environmental benefit. The stay at home lockdown however has revealed to so many of us that we can telework, at least in some sectors.

Potential benefits of teleworking:

new revenue streams for rail operators in the post-commuter age

less interaction in congested transport systems and shared working environments where contagion can spread

less money and carbon emissions expended on commuting

potentials for increased productivity

less stress by avoiding peak time travel crush, delays and cancelations

commuting time redirected to exercise, family etc.

flexible hours to help with childcare

A basic programme of accommodation might include:

season ticket holder hot desk spaces

hireable meeting rooms

printing and scanning stations

café and créche (with roof terrace space and solar shading)

indoor and outdoor exercise space

The case for a new building typology

Above: The medium to long distanced commuting towns have the greatest potentials for carbon emission savings and quality of life improvement through adopting teleworking lifestyles.

Working at home is not for everyone. Facilities can be poor and family interruptions dilute working focus. Without a change of scene, quality of life can be negatively impacted. What then if commuters did not have to commute everyday? What if season tickets could be used to travel or rent space in a rail station based facility? Such an arrangement might be financially viable as it could be paid for by moneys that would otherwise be destined for increasing transport capacity.

This new building typology, we are coining, a Node. It would be an extension of the traditional station. It would be built above station car parks or over tracks, typically in a linear format to grow with demand. It would target embodied carbon construction of below 500kgCO2e/m2, be designed for optimum deconstruction and reuse and have operational energy use of below 55kWh/m2/annum.[1] The Node would not just be a place to hot desk, it would become a community hive of activity and networking with a range of supportive facilities to make teleworking a quality of life step forward.

The proposal can play an important role in integrating pandemic resilience. The basic layout would afford inherent contagion control. It would also be able to engage active measures should a localised lockdown be imposed to allow people to continue using the facility within acceptable levels of risk.

Above & below: Elevation, long section and cross sections of ‘The Node’ complete with car and bike parking on the ground floor, serviced office space on the upper floors and with various technologies employed towards zero-carbon operational performance.

This vertical section view of the building showing some of the technical strategies for its low-energy operations, with a twin skinned facade serving as a buffer to temper replacement fresh air, reduce excessive hot summer solar radiation whilst maximising potentials for winter passive solar gains. Cross ventilation is powered with passive stack ventilation towers with rotating wind cowls serving to increase air flow.

The carbon calculation

The environmental case for The Node can be shown with the simple calculation showing the carbon emission per passenger kilometre[2]:

Brighton to London Victoria round trip = 177kms

177 km x 0.06* kg CO2/ Passenger Kilometre by rail = 10.62kg of carbon per day

253 working days per year = 2,687kg of carbon per year

On the basis that commuters might telework around 70% of the time, this would equate to carbon emission saving of around 1,881kg of carbon per annum per commuter. Naturally there would need to be some changes to the responsiveness of rolling stock to take best advantage of lower passenger numbers travelling each day.

The wider built environment ramifications

City centres would change. With businesses and organisations needing less office space and therefore less office buildings needed generally, central business districts could undergo a renaissance of downtown living. Some office building could be refitted to suit more open and flexible use of businesses whilst others could be turned into residential units and the odd disused building plot deconstructed to make way for urban lung pocket parks. Meanwhile, what were sterile weekday dormitory town centres would benefit from more locally distributed financial activity.

Architectural strategies for The Node

With a climate emergency to plan for and diminishing carbon budgets to play with, the architectural strategies for The Node need to be benchmarked as close as possible to net zero carbon as practically possible. The template for each installation will need to recognise embodied, operational and end of life carbon impacts.

Structural Strategy

Above: The structural systems proposed exploit the benefits of bio-based materials such as fast-grown cross-laminated timber superstructure with its ability for renewal and carbon dioxide capture and storage, low-carbon concrete piloti on reversible screw piles for maximising deconstruction and re-use potentials.

Reversible screw pile foundations

Ground storey piloti constructed with low-carbon concrete technology

Superstructure formed with cross laminated timber cross walls and floors with the cross walls acting as transfer beams to receive glulaminated beams to support the floor and roof decks

Apertures cut in the cross walls to have rounded corners reminiscent of apertures formed in the fuselages of planes, ships and trains from the late 1950's onwards

Environmental Strategy

Utilise passive stack ventilation with roof mounted wind cowls (safer during pandemics than air conditioning)

Post-loaded thermal mass using previously constructed sources of concrete, masonry or sand and cement screeds

Nigh time cooling of the thermal mass

Micro-louvre technology to reduce summer and mid-season solar gain through glazed apertures

Ground or air source heat pump with electric back-up for space heating and domestic hot water

Extensive on-site renewable energy systems mounted over roofs and roof terraces with 30º pitch for southerly oriented buildings or 5º – 10º pitch for east and west oriented buildings

Rainwater harvesting and high level storage to provide gravity fed toilet/urinal flushing water

Planted roof terraces to provide net-biodiversity gain over the car park

Covid responsive measures

We need to address the possibility that an effective prevention and cure may never materialise for Coronavirus / Covid-19. We must plan therefore for getting back to work with a more sophisticated and dynamic approach than purely applying the commercially disastrous two metre social distancing requirement. A significant part of this toolkit is the widespread adoption of face masks. However there maybe built-environment solutions which can help. One is to create anti-viral vestibules around entrances to buildings. These structures can be relatively easily erected with a kit of parts on the outside of the building or if the building already has a good sized draught lobby they could be retrofitted into these spaces. The idea is to create a passageway through which people move through should another outbreak arise locally, and in such situations an antiviral mist can be sprayed to treat everyone entering the building at times of heightened risk.

Above: The basic layout of the hot desk spaces relies on discrete screens either side to form niches which might largely contain aerosol-borne contagion with no one facing someone else. If local virus outbreaks occur, work stations would be misted with an alcohol spray between use and wearing of face marks made mandatory.

Combined with automated temperature checking, the use of hand wash dispensers at entry points and the ubiquitous wearing of face masks, it should be possible to remove social distancing requirements such that pretty much all commercial activity can continue within acceptable risks. For The Node, these measures would be integrated from completion. Additionally each hot desk space would be created as a discretely enclosed niche to help contain contain any virus laden aerosol from occupants. During any new outbreak, hot desk spaces can be treated with anti-viral alcohol-based misters after use with the cleaning staff able to electronically update when a particular workstation is available. In this way the environment created reduces risk of spreading contagion but if a local outbreak happens, further measures can be easily implemented.

[1] RIBA 2030 Climate Challenge target metrics for non-domestic buildings, RIBA Sustainable Outcomes Guide 2019

[2] http://www.aef.org.uk/

Switching from a gas boiler to a heat pump

Should I be switching my gas (or oil-fired) boiler for an electric heat pump? It is a question a lot of people are asking and the considerations involved in answering it are not entirely straight forward. For years, the adage has been, “if you are on mains gas, then don’t change to a heat pump”. As the electricity grid continues to reduce its carbon intensity, that argument is becoming increasingly tenuous and soon it will be just plain wrong advice both in terms of cost in use and relative global warming potentials. Let us have a look at some of the issues involved and compare how gas or oil-fired boilers and electric heat pumps work.

“A heat pump is in principle a refrigeration cycle operating in reverse by extracting heat from a low-temperature source and upgrading it to a higher temperature for heat emission or water heating. The low-temperature heat source may be from water, air or soil which surrounds the evaporator.”[1]

Introduction

Should I be switching my gas (or oil-fired) boiler for an electric heat pump? It is a question a lot of people are asking and the considerations involved in answering it are not entirely straight forward. For years, the adage has been, “if you are on mains gas, then don’t change to a heat pump”. As the electricity grid continues to reduce its carbon intensity, that argument is becoming increasingly tenuous and soon it will be just plain wrong advice both in terms of cost in use and relative global warming potentials. Let us have a look at some of the issues involved and compare how gas or oil-fired boilers and electric heat pumps work.

Gas boilers and heat pumps briefly explained

Most of us are familiar with a gas boiler. By definition, a boiler heats water for use in space heating and the domestic hot water supply. Very similar boiler designs are used to work off liquid propane gas (LPG) and domestic heating oil. Some are designed to work with a hot water cylinder whilst others, known as combination boilers, make the hot water for immediate use in the property. Most boilers in the modern era work off a balanced flue whereby intake air comes in around a sleeve containing the hot exhaust gases. The most efficient are condensing boilers whereby that exhaust gas provides something of a preheat to the cool water return pipe. In so doing it the water vapour in the combustion gases condenses and thus the name. These generally have rated efficiencies of up to 90% although the real-world figure is likely to be more like 85%. A typical installation cost might be between £1,900 to £3,000 depending on the make, range and power output.

The essential difference between a gas boiler heated home and an air source heat pump heated home is that the heat pump would struggle to make 70ºC water and as such the house itself needs to have a reduced rate of heat loss (usually requiring some thermal efficiency upgrades to the external building fabric) and having larger ‘heat emitters’ like underfloor heating and extra large radiators.

Heat pumps are electrically driven. Essentially they work very much like a refrigerator in that they take heat from one area and release it in another area. In most cases a heat pump for a building will transfer heat from outside air and concentrate it into a hot water cylinder inside the property. This would be an air to water heat pump. Air to air heat pumps are also quite common and often used in commercial premises. For those with deeper pockets and a context which allows for the physical interventions required, there are also ground source heat pumps and even water source heat pumps. In most cases, these more expensive units have lower running costs and you will see that quoted in the equipment’s declared ‘coefficient of performance’ or CoP for short. More on that later.

The main heat source varieties of heat pumps for buildings.

To do this thermal-dynamic alchemy, they use a refrigerant gas in a closed circuit and a compressor, just like a fridge. The electrically driven compressor has the effect of raising the temperature of the refrigerant so that even if say the air outside is 5ºC, it can raise water temperatures in the tank to around 40ºC via a heat exchanger. Amazingly a typical air source heat pump produces about three units of heat for every unit of electricity inputted.

Physically, a gas boiler for a private residential premises will be wall hung and can easily fit within a 600x300x900H mm wall cabinet so it can be seamlessly hidden in a kitchen, utility room or airing cupboard in a most unobtrusive manner. A heat pump on the other hand needs more thought about its spatial requirements. An air source heat pump has an external unit about the size of an old pavement mounted telephone exchange, typically 1000x300x1000H mm. The hot water cylinders which work with heat pumps also have extra kit on them so possibly a little larger than people are used to. With ground source heat pumps there is no ‘external unit’ as such but you still have to have a hot water cylinder and a circulation pump unit which is usually floor standing and about the size of a large fridge freezer.

For a private residential project, the cost of an installed air source heat pump (ASHP) might be in the region of £10K to £13K whereas the cost of a ground source heat pump (GSHP) is typically around £25k - £40K depending on the size and type of installation.

Ground source heat pumps normally require a significant amount of external space to be created. This is needed either for the borehole typology whereby the heat is extracted with the ground down to perhaps 100+m below the surface. Alternatively, there is a horizontal type with relatively shallow excavations needed to install a pipe working just out of reach of winter frost ground penetration. Generally, this type needs a very large external area to work within.

Operationally, probably the most important difference between a heat pump and boiler is that the later works with an ‘energy dense’ fuel source such as gas or oil and has no difficulty at all in raising water temperatures to around 70ºC. A heat pump, on the other hand, will struggle to get water temperatures above 40ºC. The knock-on effect is that it is usually necessary to increase the size of the heat emitters in your home (ie. Radiators) or put underfloor heating in. Furthermore, if your house has single glazing and is poorly insulated then you might struggle to have a heat pump at all. As a rule, you should reduce the rate of heat loss in your home to a point whereby a heat pump can efficiently maintain thermal comfort conditions.[2]

When is the right time to switch to a heat pump

So, the key message is – if you do nothing else, make enough fabric improvements to switch to a heat pump and avoid putting in fossil-fuel systems at all costs.

LETI, LETI Climate Emergency Retrofit Guide, October 2021. Pg. 9[3]

This illustration shows relative costs of eco-retrofit investment with running costs over time showing the cumulative effect of each measure. This is set against retention of a gas boiler, the fuel source of which, is likely to be subject to more cost inflation as global supplies diminish. The more energy efficient the building, the more protected the occupants will be to rising energy costs. Projections beyond 2022 (Year 1) are speculative.

The big question is, when is the right time to make the switch to a heat pump? If you already have a well-insulated house, it might be that you should crack-on and get one put in soon. If not, best to wait until you have made at least some basic thermal efficiency improvements.

There are two other issues to consider. One is the cost of the fuel source and the other is the relative environmental impact which is usually expressed as ‘CO2e’. It is a measure of global warming potential.

According to the Energy Saving Trust who do a useful online comparison, as of October 2022 it is still slightly cheaper to run an A-rate gas boiler over an ASHP, but cheaper than almost any other form of heating.[4] Curiously, domestic heating oil is now about the cheapest form of heating whereas in the early 2000’s and within the space of a few years, its cost increased over 400% and led many off-grid homeowners to carry out deep retrofit makeovers of their homes. However, if you want to do the right thing for the planet and reduce overall carbon emissions, an ASHP is already rated better than all other heating typologies.

This illustration depicts how gas boilers are no longer as carbon beneficial for providing heating as heat pumps. A similar tipping point is shown for the relative fuel cost. Note the effect of the war in Ukraine. Projections beyond 2022 are speculative.

According to provider Bulb, UK electricity production went from 0.233 kg of CO2e per kWh in 2020 to 0.193 kg in 2022.[5] This reduction is down to more renewable sources of energy production, like wind turbines and solar panels, coming online and increasing their share in the national electrical grid. This is known as the ‘carbon intensity of the grid’ and it is important as, up until recently, it was more carbon beneficial to have an efficient gas boiler doing your home heating rather than a heat pump. As recently as 2014, a respected information source on eco-retrofit stated, “With the current mix of fuels for electricity production, heat pumps result in approximately the same fuel costs and levels of emissions as heating by gas-fired condensing boilers, so it is not appropriate to install heat pumps in dwellings that have mains gas supplies.”[6]

That is largely because for every unit of grid supplied electricity coming out of your plug socket, about three units of power are required to make it back at the power station. It is to do with losses in conversions and the power being bumped-up and then bumped-down as it is passed around the grid’s distribution infrastructure. To illustrate the point, think how much more efficient it is to burn a unit of gas to make heat in your home in a boiler than burning the same unit of gas at a power station to make electricity which you then use in your home to make heat.

So, whilst it has very recently become more carbon beneficial to heat your home with a heat pump than a gas boiler, we are approaching a similar tipping point whereby it will soon be cheaper in running costs as well.

Shifting sands and diminishing returns

We have already looked at how the carbon intensity of the grid has been lowering and thus making the case for switching to a heat pump stronger. It is also useful to check what forms of Government subsidy might be available for an ASHP installation. Sadly, there is very little financial help left with the Feed-in Tariff scheme ending back on 31 March 2019 and the Government’s reduced VAT rate of 5% is no longer available to all income groups for eco-retrofit work. Happily, as of October 2022 there are still grants available for ASHPs under the Boiler Upgrade Scheme of £5,000 and of £6,000 for GSHP. It is always worth doing fresh research on this when you make your evaluation.

Curiously, if you have shelled out tens of thousands of pounds on eco-retrofitting lots of insulation and replacement double or triple glazing to your house, to then fit an ASHP will in effect constitute a diminishing carbon v cost return. Say you reduce your heating demand by 75% with thermal efficiency upgrades, the heat pump can then only provide an efficiency saving on the remaining heating demand which might be awkward for those who fuss over pay-back periods.